James Joseph Tunney III, better known as Jim, or simply Number 32, has made his final exit from the field in Pebble Beach, California, with his loving wife Linda and family members at his side.

James Joseph Tunney III, better known as Jim, or simply Number 32, has made his final exit from the field in Pebble Beach, California, with his loving wife Linda and family members at his side.

He had, in his words, “reached daylight” on March 3, 1929 in Hollywood, the first-born son of James Joseph Tunney II and Katherine Brubaker Tunney, and he remained bathed in its shine for 95 bountiful years, loved, admired, and depended upon by a community of family, friends, and professional colleagues nationwide and beyond.

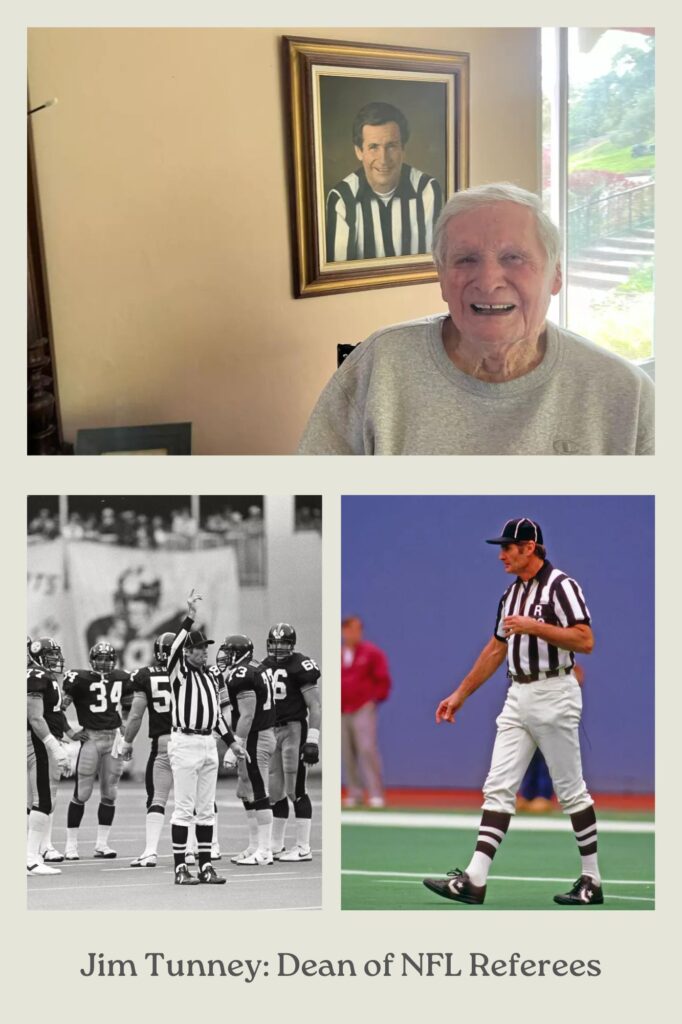

Jim Tunney was a respected NFL referee, a masterful public speaker, an educator, an author, a coach, and the very proud father of Maureen, Michael, Mark, Janet, and Debbie, with a gift for bringing people together. Most of the world knows him as an arbiter of goodwill and excellent competition on the gridiron, standing tall to signal with slowly unfurled fingers (or not) the fate of a leather oblong ball pitched or kicked into the endzone on a Sunday afternoon, or explaining the certainty of a particular rule’s application to the event that just unfolded. Stadiums full of people alternated between agreement and disagreement with his pronouncements over the decades, and the debates carry on to the present day. His integrity, though it might have been obscured by the fog at times, remained unshakeable. He earned, honorably and consistently, the title bestowed upon him by Los Angeles Times sportswriter Bob Oates, Jr. in a story published on the date of Jim’s second Super Bowl appearance in 1978: “The Dean of NFL Referees.”

Jim Tunney was also a mensch who could be counted on in a thousand other circumstances. Those long arms could wave hello from across the yard, pick up a giggling toddler, carry a stranger’s bags, or toss a hot dog to a hungry young buddy at a Little League game. He was a foundational supporter and representative of the Southern California Special Olympics. His Youth Foundation, begun in 1993, opened up athletic doors to a couple of generations of kids, providing them with equipment and exposure to professional sports heroes attending annual banquets on the Monterey peninsula.

A longtime member of the National Speakers Association, in 2007 he received its Philanthropist of the Year Award for the example he set as a giver, a teacher, and a catalyst for doing the right thing. In 1989 celebrated former coach and CBS announcer John Madden, a friend and neighbor on the Monterey Peninsula, honored him with one of the inaugural All-Madden Awards for outstanding work on the field. In 2002 the NFL Alumni organization presented him with the Order of the Leather Helmet for his service to its members. The list of honors continues, for everywhere that Jim Tunney turned his attention he saw an opportunity to practice the acronym that had become his message, his motto, through 30 years of motivational talks: “T.E.A.M,” or “Together Everyone Achieves More.”

Jim’s father had been an educator and sports official and he followed along that path, with both worlds rising in national prominence in California during that era. He was a product of Franklin High School in Highland Park in 1947, and received his bachelor degree from Occidental College in 1951, from which he later earned a Gold Seal Award for outstanding achievement as an alumnus. (In 1975, he would be awarded a doctorate in education from USC.) He went to work as a teacher and coach, and soon began to supplement those jobs with officiating, first at the high school level and in due course graduating to college and the Pac 10.

By 1960 his work in the college game, which included Rose Bowl assignments, caught the notice of the NFL and he was hired as a field judge. Jim’s maternal uncle Harry “Bud” Brubaker, on the same career arc as the Tunney men, had preceded him by 15 years as an NFL referee, and mentored him colorfully and capably on the field. Seven years later Jim was promoted to referee, and remained in that role until his retirement in 1990.

During his early career, juggling those teaching, coaching, and officiating jobs and striving to establish his professional identity, Jim married his college sweetheart Marie Picou, and the family has grown and changed through the decades into an expansive roster comprising grandchildren, great-grandchildren, cousins, in-laws, and blendees hailing from Jim’s later marriage to Linda Broughton in 1996. Then there were his own siblings Joanne, Peter, and Loretta, and all of their issue, and it would require Census Bureau overtime to count, much less name, everyone in that multi-generational crowd. Suffice to say the extended Tunney clan covers substantial territory.

Speaking of which several Tunneys, along with their Brubaker kin, got into the California horse racing business, starting with Jim’s paternal uncle Willard, who became the general manager for Bing Crosby and his hoof-pounding cronies when Del Mar opened in 1938. Jim’s father was called in after a couple of racing seasons, as a respected official, to quell a growing foul problem at Del Mar and later served as a steward at Santa Anita until his death in 1965. Bud Brubaker paralleled his officiating job at Del Mar, where he began in 1945 and eventually served as operations manager until his retirement. Jim’s late younger brother Peter, a running back signed by the Detroit Lions, left football after a crippling leg injury and heeded the bugle call at various California tracks before serving as the general manager/executive vice-president at Golden Gate Fields from 1980 to 2017. And Jim’s son Michael has worked at Del Mar for a story-filled 40 years.

Aside from the highlights his career as an official produced, with 29 post-season assignments, 10 championship games, and three Super Bowl appearances–two of them in consecutive years, a feat so far unmatched–Jim pursued a simultaneous career as a teacher and educational administrator (NFL officiating remains to this day a part-time job). In a jacket and tie rather than pin stripes he served as the principal at Fairfax, Franklin, and Hollywood High in succession from 1964 to 1974, as the Bellflower District Superintendent in 1977, and 16 years later as the temporary headmaster at the York School in Monterey. He was also a trustee at Monterey Peninsula Community College from 1997-2009, for six of those years sitting as the board chairman.

In 1960, Jim was approached by the president of his local Kiwanis Club and asked if he would spice up its weekly luncheon with a few “jockstrap stories.” The young official was of course obliging, but his presence at the microphone led to further meditation on the transaction between speaker and audience. The early engagements grew in frequency, with each talk different and tailored to the character of the crowd he was addressing, but as he expanded his bookings to companies and organizations from coast to coast he found a unifying theme in supporting the company mission, and encouraging teamwork with every single group he stood in front of. During his long, well-traveled speaking career he accumulated more than 4,000 engagements.

Public speaking led to some interesting destinations for Jim, including a handful of cruises on which he shared the microphone duties with Don Shula (accompanied by their wives Linda and Marianne), the retired coach of the Miami Dolphins who became a close friend and neighbor in later years, any lingering on-the-field disagreements tossed into Davy Jones’ locker. He developed other meaningful relationships over the years with people at the top of their fields, which is a modest description of his pal Frank Sinatra. And there was the beloved Vin Scully, who sought Jim’s tutoring in football prior to his seven-season recruitment as an NFL announcer, and who remained a good friend to the end of his life. Jim also counted Paul Salata, an enterprising California businessman best known for his creation of the “Mr. Irrelevant” award to honor the last pick of the NFL draft each year, as a reliable and always-surprising friend since their first meeting at a convention in 1953. The same was true of Bob Boyd, a childhood friend and teammate who became the colorful head basketball coach at USC. And there has been, in more recent years, the addition of CBS broadcaster Jim Nantz to the pantheon of friends admired and respected by Jim Tunney.

While he was the principal at Fairfax High (where in 2010 he was inducted into its Hall of Fame) Jim got to know alumnus Herb Alpert, co-founder of nearby A&M Records and the leader of the Tijuana Brass, who would arrange to have his band and other artists make periodic fundraising appearances for the students. This relationship–deepened when Alpert asked Jim “Why don’t you come to work for me?” and Jim replied “All I play is the whistle. What can I do for you?”–led to an ongoing colloquy between the two men about the ideal learning experience, and when Jim’s term at Fairfax ended he did indeed go to work for the Alpert Family Foundation. While this interlude did not result in the prototype alternative school that had been a goal of the foundation, it made a significant contribution to the California dialogue about innovative education and helped inform Jim’s subsequent work as the principal at Hollywood High.

No account of his years at Hollywood High would be complete without recalling one of Jim’s most memorable responses, delivered to a streaker racing around the Hollywood Bowl in the middle of the 1974 graduation ceremony. As the student with the pronounced craving for attention paraded across the stage, streamers flying, Jim raised his microphone and called out “Hey, you forgot your diploma!” (As it turned out, his diploma was conferred by Principal Tunney only after the streaking senior presented him with a letter from a future employer attesting to his passable character.) Jim remains a respected, fair, and jovially communicative figure in the memories of a multitude of students who attended the schools he served, the majority of whom remained fully clothed during their own graduations.

Jim Tunney was an accomplished author and essayist alongside his public speaking. Beginning with his Impartial Judgment in 1988, he wrote or co-authored nine books including Chicken Soup for the Sports Fan’s Soul (which for a time occupied a spot on the New York Times bestseller list) and It’s the Will Not the Skill, (his ode to the values he observed–and shared–with former NFL player and coach Herman Edwards). The column that he produced weekly for the Monterey Herald until just months ago, On the Tunneyside of Sports, was also published in collected book form on multiple occasions. His written work generally followed the motivational theme that was his hallmark as a speaker, and pointed to an energetic and irrepressible part of his nature, which was the fire that he carried for the welfare of everyone. He staked his success on this sphere to whatever contribution he could make to your own, directly or indirectly.

His columns were all assembled around a thought, an observation, a reservation, or a celebration that was foremost on his mind in any given week, and the depth and variety of all that subject matter was a testament to the dilemma and promise of the times in which we live. He always presented his reader with a blunt rhetorical question at the conclusion of each column, a motivational coda that doubled down on the subject at hand, e.g., Will you allow your dreams to lead you to action, participation, and commitment in your life?…Will you prepare thoroughly so that you’re ready when the moment arrives?…Will you help others who may be facing a difficult situation to find the courage within?

It was his way of taking it directly to you. It was a steadfast and supportive voice that echoed through decades and generations, and it will be missed.

In lieu of flowers, consider honoring Jim’s memory with a donation to the Special Olympics of Southern California or to any other youth sports organization that holds special meaning for you.